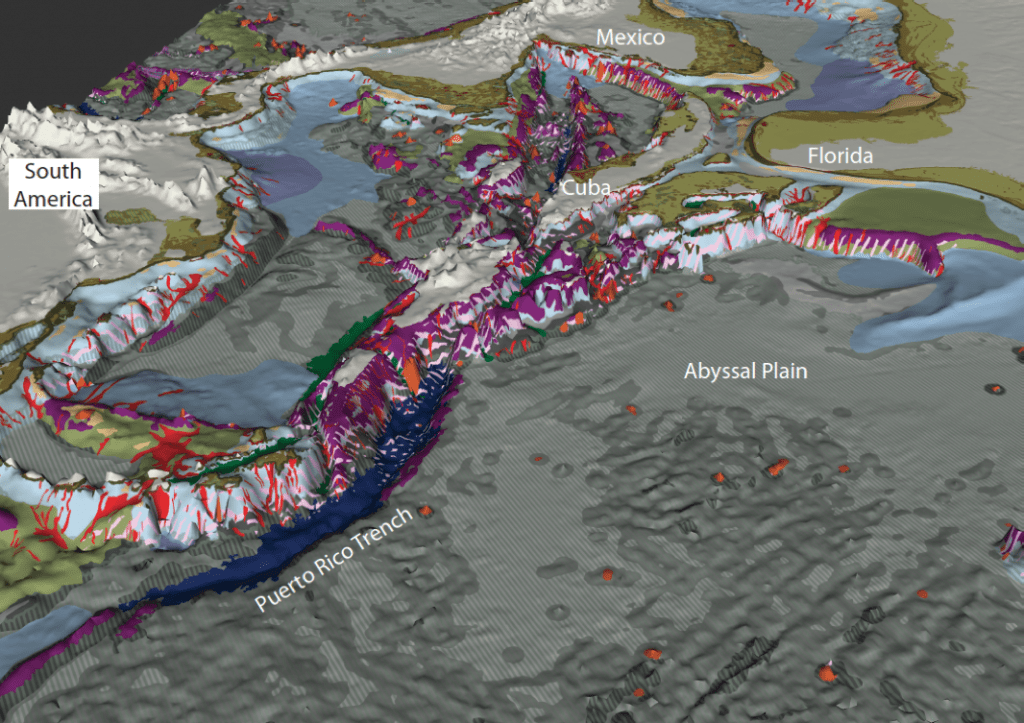

Trenches – Trenches are “a long narrow, characteristically very deep and asymmetrical depression of the sea floor, with relatively steep sides” (IHO, 2008). Trenches are generally distinguished from troughs by their “V” shape in cross section (in contrast with flat-bottomed troughs). The upwelling of basaltic lava on the mid-ocean ridges gives rise to the formation and lateral spreading outwards of ocean crust. The tectonic movement (or “drift”) of continents, driven by seafloor spreading, results in two fundamentally different kinds of junction where ocean and continental crust are in direct contact: active and passive plate margins. Along active plate margins, the ocean crust collides with and is over-ridden by continental crust (or in some cases by less-dense ocean crust) in a region called the subduction zone, where ridge and trench complexes are created. This occurs because the denser ocean crust is subducted beneath the lighter continental crust (forming a “V” shaped trench) and the lateral pressure pushes the continental crust upwards (forming a ridge). In some locations, ocean crust is subducted beneath other ocean crust, so not all subduction involves continental crust.

Ocean trenches are the deepest parts of the ocean, commonly 6 to 10 km in depth[1] and have a highly specialised fauna. Trenches are separated from each other by comparatively shallow ocean floor over which any trench-associated animal would have to pass, and so trenches are isolated from each other. This isolation has given rise to a high degree of endemism for trench fauna. Oceanographic conditions vary between trenches, but generally species diversity decreases with increasing depth, with a high percentage of species endemic to individual trenches (Gage and Tyler, 1991). Most of what we know about ocean trench fauna was derived from Danish and Russian expeditions carried out in the 1950’s and 60’s, during the “heroic” era of deep sea exploration (Gage and Tyler, 1991), that culminated in the 10,911 m decent of Jacque Piccard and Don Walsh aboard the bathyscaphe Trieste on 23 January, 1960 to the bottom of the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench. Looking out of the Trieste’s porthole, Piccard observed a solitary flat bottom fish[2], confirming the existence of life at even the greatest ocean depths. Species most common in the hadal community are molluscs, polychaete worms and particularly holothurians (Jamieson et al., 2010).

Sediment that is eroded from areas of surrounding seafloor slumps down into the trench as debris flows or turbidity currents. Over time, sediment may partially infill the valley to form a flat-floored trough. Along passive plate margins there is no subduction zone (or trench) and the oceanic and continental crusts simply abut one another; there are thus no trenches or troughs along passive margins.

[1] The Mariana Trench in the Pacific Ocean is the deepest place in the world ocean at -11,034 m water depth.

[2] Wolff (1960) suggested Piccard’s “fish” was more likely to have been a holothurian since flatfish are uncommon below ~2,000 m depth.